This month, Jean de Rusett explores the role that Shropshire played in the escape of the young Charles II from the Parliamentarian forces after the Battle of Worcester, when he hid at Boscobel House, and amongst the branches of the famous ‘Royal Oak’…

This month, Jean de Rusett explores the role that Shropshire played in the escape of the young Charles II from the Parliamentarian forces after the Battle of Worcester, when he hid at Boscobel House, and amongst the branches of the famous ‘Royal Oak’…

Our fugitive’s father was King Charles I, the only British monarch to be executed at the whim of Parliament. Charles I ruled for eleven unsettled years. His grip on power started to crumble when, having failed to call a Parliament for ten years; he then tried to thwart proposed parliamentary reforms. The country divided into two camps: the Royalist ‘Cavaliers’ supporting the King, and Cromwell’s Parliamentarians ‘the Roundheads’ opposing him, and a bloody and turbulent Civil War ensued. It ended with Charles I’s public beheading in January 1649 and the country became a Republic headed by Oliver Cromwell.

At the time of his death, Charles I’s wife, Henrietta Maria and their five children were in exile on the Continent. His eldest son, the nineteen year old Charles learned of his father’s death by of his Chaplain addressing him simply as ‘Your Majesty….’

Charles II bided his time, negotiating to raise an army in order to regain his throne. In 1651 he landed in Scotland and got as far south as Worcester, where his Royalist troops were overwhelmed by Cromwell’s forces on 3rd September. The gallant young King had been in the thick of battle throughout, but managed to escape with a band of supporters.

It was fortunate for Charles that amongst his entourage was Charles Giffard, owner of Chillingham Hall in Staffordshire, and Whiteladies Priory and Boscobel House in Shropshire, the latter properties buried deep in the dense Brewood Forest, and it was to here that the group fled. Better still for Charles, the Giffard family were Catholics in an era of Catholic persecution, so had surrounded themselves with servants and tenants who were discrete and reliable, foremost among them the Penderel* family, who lived at Whiteladies, Boscobel.

Under cover of darkness, Charles and his small party made their way north, arriving at Whiteladies Priory at dawn on the 4th September where Charles discarded his fine clothes. In order to disguise him, his luxuriant hair was cut short and he was dressed in woodcutter’s clothes. He was a tall man, so shoes were the biggest problem as he had such large feet; he suffered agonies walking miles in ill-fitting shoes. After a brief meal, it was felt the safest option that he hide in the woods during the day. By this time there was a £1000 ransom on Charles’ head – a huge sum in that day.

Under cover of darkness, Charles and his small party made their way north, arriving at Whiteladies Priory at dawn on the 4th September where Charles discarded his fine clothes. In order to disguise him, his luxuriant hair was cut short and he was dressed in woodcutter’s clothes. He was a tall man, so shoes were the biggest problem as he had such large feet; he suffered agonies walking miles in ill-fitting shoes. After a brief meal, it was felt the safest option that he hide in the woods during the day. By this time there was a £1000 ransom on Charles’ head – a huge sum in that day.

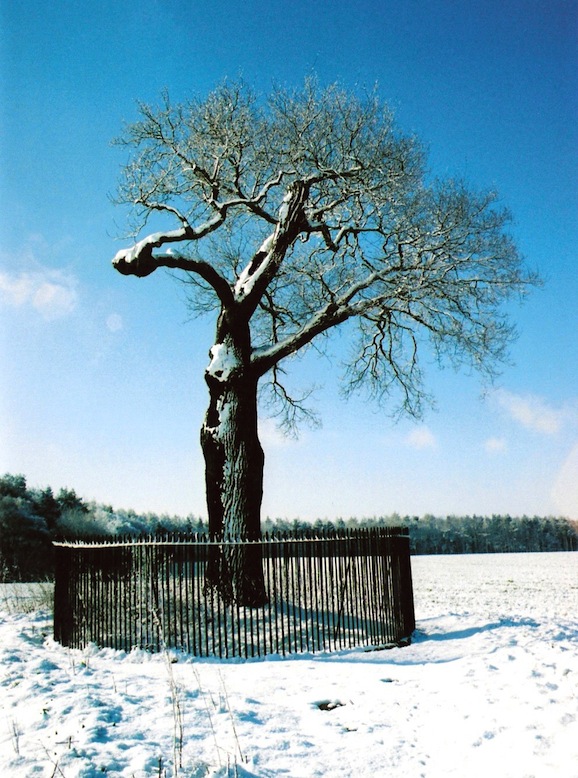

That night, accompanied by Richard Penderel, Charles tried to cross the River Severn at Madeley, but all the crossings were too well guarded, so after a night in a barn they retraced their steps to Boscobel, where Colonel William Careless** who had also escaped from the Battle of Worcester, was hiding. To avoid detection from the Parliamentarian troops, who would be sure to search the house, Charles and Careless spent the day concealed in the branches of a large oak tree 150 yards from the house, from which they saw troops searching the woods for them. At night Charles wedged himself into the tiny Priest’s hole in the attic, which can still be seen today.

After three days in hiding at Boscobel, Charles was guided to another safe house, Moseley Old Hall, five miles away, so ending the Boscobel escapade. Charles eventually made his way to Shoreham in Sussex and found a boat to take him to France, arriving at the French Court emaciated and dirty. Charles had to wait another nine years before setting foot on English soil again, when, in 1660 the Monarchy was restored and Britain concluded its only time as a republic.

In 1810 the Boscobel estate was sold to Henry Evans of Derbyshire. He developed a model farm and promoted its links with Stuart history. English Heritage now manage Boscobel and Whiteladies Priory – do go and visit, you won’t regret it.

By 1712 this oak was in a sorry state. With the Restoration of Charles as King in 1660, the Royal Oak became, and remains, a tourist attraction. Enthusiastic tourists lopped off souvenir samples and eventually the oak died. The present tree was grown from one of its acorns, but it too is in a state of terminal decline having been struck by lightning a decade ago and is now girdled by metal bands.

By 1712 this oak was in a sorry state. With the Restoration of Charles as King in 1660, the Royal Oak became, and remains, a tourist attraction. Enthusiastic tourists lopped off souvenir samples and eventually the oak died. The present tree was grown from one of its acorns, but it too is in a state of terminal decline having been struck by lightning a decade ago and is now girdled by metal bands.

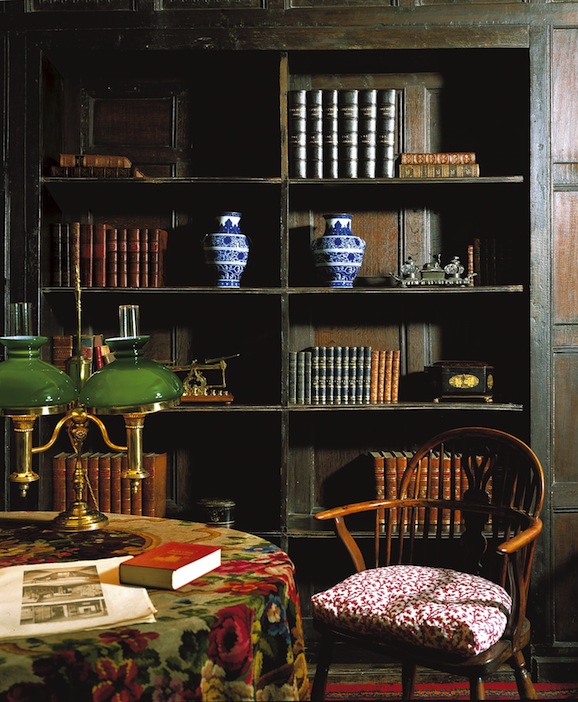

Boscobel House was initially a timber framed modest farmhouse, but John Giffard had added to it, converting it into a hunting lodge with a parlour and bedrooms in 1632. Whiteladies Priory had housed Augustinian nuns since the mid-12th century, until Henry VIII’s suppression of religious houses in 1536, when it came into the hands of Edward Giffard, who built a substantial timber framed house and outbuildings alongside the ruins of the priory. Sadly nothing remains of this beautiful house now. There is a painting at Boscobel depicting both properties in 1651, indicating they are separated by only a short distance: this is artistic license as they are in fact over a mile apart.

Jean de Rusett

Boscobel House & The Royal Oak, Bishop’s Wood, Shropshire ST19 9AR Tel: 01902 850244 or visit www.english-heritage.org.uk for winter and summer opening hours.

*Pendrill, or Pendrell **Carlos or Carliss