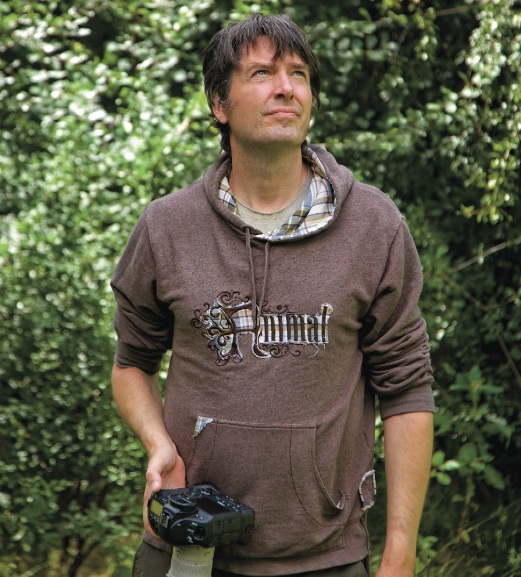

Poet, author and wildlife photographer Andrew Fusek Peters lives in the very heart of south Shropshire. It was following a bout of severe clinical depression that he took up photography as a way, he says, of “reconnecting with his surroundings”… and he has never looked back. Having been shortlisted for numerous categories in the British Wildlife Photography Awards, Andrew is currently in the running for Amateur Photographer of the Year – and his shots have also graced our very own cover.

“I’ve always loved wildlife and now I have a chance to express that,” says Andrew, who has also been volunteering with Cuan House Wildlife Rescue in Much Wenlock. “I’ve been trying to help raise awareness of the incredible work carried out there – and I’m delighted that a shot I took of a rescued tawny owl has been published in the prestigious magazine Amateur Photographer.”

Here Andrew shares his personal experience of capturing on film the elusive kingfisher deep within a secret location on the Shropshire borders…

Azure encapsulated

In my younger days, I was fascinated by blue – I bought my new wife a necklace of lapis lazuli beads, so perfectly round and with such colour it was as if the circumference of the sky were contained within. No wonder the Old Masters ground the stone for their paint; if they could have distilled the feathers of the kingfisher, the results would have equally stunning.

What had I seen of this river bird as I went for my frequent Shropshire wild swims? Nothing but the odd blur, a zip of contained colour so fast it was said to be able to ward off Zeus’s lightning. Oh and once on a far stick perch, a bright blue blob small and impossibly vibrant when all around was dulled to a khaki of green and brown.

As a fledgling wildlife photographer, still trying out his wings, I had sat in official hides on well known reserves where all my skill netted me a silhouette on a stick and yet more frustration. How could such colour be so elusive?

A guiding hand

A guiding hand

Then I met my army veteran ‘friend’, who will remain anonymous. Here was a mate-in-the-making who understood the behaviour of these secretive birds, each pair commanding a kilometre or so of river, along which mounds of clay and overhanging bushes were regular perching, fishing, diving and preening spots.

I found myself inducted into the art of surveillance: how to set up camouflaged hides to give the best view over the watery A-Z that kingfishers patrol. For, like all the animals who tread warily around us human colonisers, they rely on pattern and behaviour. Just as we like our favourite coffee shop on a certain day, so the kingfisher will come back to a perch almost like clockwork if we do not disturb it.

Getting close is the grail, to shrink that far blur into a still life that bursts from the camera’s playback screen. The work is no mean task. Hours, days, weeks of patience, of endless visits where nothing much happens, where camera doesn’t focus in time, or the light is wrong, or the kingfisher decides on a perch just round the river bend and our lens cannot see round corners.

Close to the edge

On this particular day, after three hours of cramp and missed opportunities, I was ready to call it a day. I was almost weeping with frustration. But we have friends for a reason, and my sage pal told me to ‘think’. It calmed me, we carried on; him in full-on army surveillance gear… me in my pop-up tent on the pebbles of the river bank.

Kingfisher came down, the lapis of the earth ground into his wings, fish in beak, not more than ten feet away from me. He knew I was there, but was not bothered nor distressed. Somewhere, not far away, the fledglings were ready to be fed and, it turns out, fly the nest that next morning. But for now, he posed, the sky on his back, the orange sun of his beak, the glistening silver of the fish he’d dived for. King of the fishers – as the poet Frederick William Faber said, “There came, swift as a meteor’s shining flame, a kingfisher from out on the brake, and almost seemed to leave a wake, of brilliant hues behind.”

Andrew’s book In Wilderness Is Paradise Now – Words and Wildlife from the Borders will be released in 2016.

Andrew’s book In Wilderness Is Paradise Now – Words and Wildlife from the Borders will be released in 2016.

His memoir Dip: Wild Swims from the Borderlands is published by Rider Books, Random House and has featured on The One Show, You Magazine, and BBC Radio.

Andrew has been commissioned by the National Trust and Natural England for their new project ‘Stepping Stones’, to celebrate species and landscape between the Stiperstones and the Long Mynd.