In this issue, Ed Andrews takes to the waters of the mighty Severn to experience nature from a different angle.

Ironbridge Coracle Regatta takes place every year on August Bank Holiday Monday. This year I entered in a coracle made by my father-in-law. Hundreds of people lined the riverbank to watch the regatta. Novices like me could try and master the tricky art of paddling a coracle while the more experienced coracle men and women could take part in a series of fun races and challenges. The event celebrates an Ironbridge way of life that sadly is no more.

The Rogers family were building coracles in a shed that sat in the shadow of the bridge for at least 250 years. The last Severn coracle-maker, Eustace Rogers, passed away in 2003. The coracle is one of the earliest forms of vessel and examples can be seen from all around the world. They would once have been built from natural materials such as woven willow and animal skins. Eustace Rogers used strips of ash skinned with calico cotton and painted with tar. Our coracle was built using the same method, but ash was substituted for more readily-available birch ply (cut into strips).

Versatile vessels

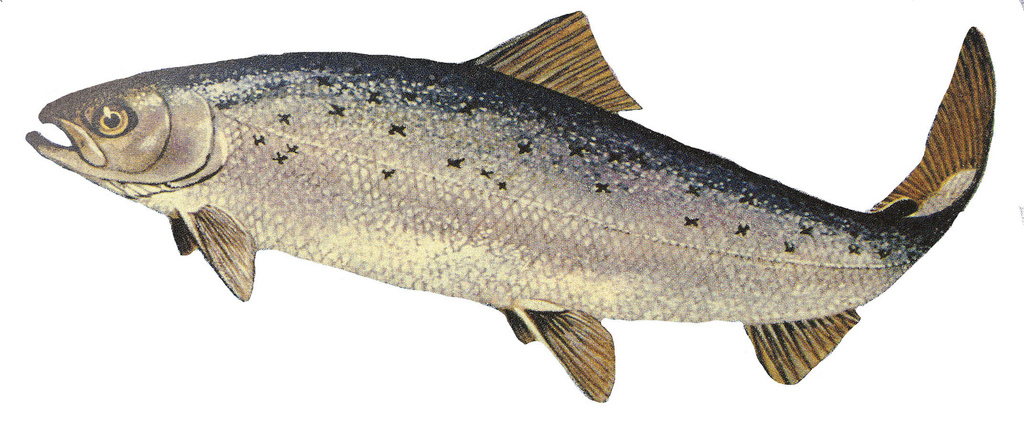

Severn coracles were used for transport and fishing. Skilled coraclemen paddled with one hand, leaving the other free to fish. Typically coraclemen would work in a pair with the net strung between them. Their prize quarry would have been salmon. Salmon start their life in the river. After two or three years, they migrate to the Atlantic to mature. They spend five years at sea before returning to the river where they were born.

As the autumn rains cause the Severn to swell, the salmon move upstream to start spawning through November and into December…

They typically begin appearing in the estuary from early summer. As the autumn rains cause the Severn to swell, the salmon move upstream spawn through November and into December. The seasonal movement of salmon up the Severn was a bounty for the coraclemen.

Waterborne views

I am drifting along a shallow section of the river, just downstream from Bridgnorth. An autumn breeze ruffles the surface and shakes the overhanging boughs. The coracle resembles the upturned leaves that decorate the clear water around me. In the gravel beds below, the female salmon will dig a ‘redd’ (shallow depression) with her tail before laying thousands of eggs into it. The male then fertilises the eggs.

I reach into the water and pick up a piece of broken china from the gravel. China clay was imported from the south west and turned into fine, exquisitely painted chinaware at busy Coalport. Thousands of pieces of broken china from those days now lie throughout our stretch of the river. The edges of my piece have been worn smooth and the surface is the home to tiny water snails and an aquatic flatworm. I float over a bed of pea-green streamer weed, gently oscillating in the flow and making valuable cover for fish. I paddle to a shingle beach and haul out before walking back upstream.

Regal colour

I launch again but this time paddle hard to a deeper section of water. In 2013, a 34lb salmon was caught from the Severn. I peer into the oily depths and imagine these river monsters swimming beneath me. Past the tips of willow branches hanging in the water, I pass a storm drain. Perched on a branch is a kingfisher. I paddle against the flow for a minute to hold my position. Under a grey sky his azure blue plumage seems to radiate energy. He nods his head up and down to accurately gauge the position of fish under the water. The kingfisher does not seem concerned by my presence. From the water, I can admire the architecture of the willow roots. The exposed bank between the roots will make a great place for the kingfisher to nest next spring. First he has a winter of ice and floods to get through.

From the water, I can admire the architecture of the willow roots…

Coracles are shallow drafted, so can cope with shallow sections of river with ease. The lack of wake minimises any potential disturbance to fish and wildlife. They are also extremely manoeuvrable. With a flick of the paddle, the coracle will spin 360 degrees. Importantly they are also small enough to be shouldered and carried along the riverbank. These reasons make coracles great vessels for both fishing and wildlife observation. Often when walking alongside the river, one disturbs a bird or hears a splash as an animal has quickly disappeared. By entering the river kingdom in a coracle and immersing oneself in the habitat, it has proven possible to get much closer to river wildlife.

Do one thing for wildlife this month…

Ironbridge Coracle Trust are working to safeguard Eustace Rogers’ shed and commemorate the heritage of coracle-making on the Severn. They have already managed to purchase the shed and are now trying to raise funds to create exhibits. For maximum success, the project needs local people to get involved. Why not check out their webpage at coracleshed.org, make contact via social media or complete their online questionnaire?